Niagara's Ice Mountains

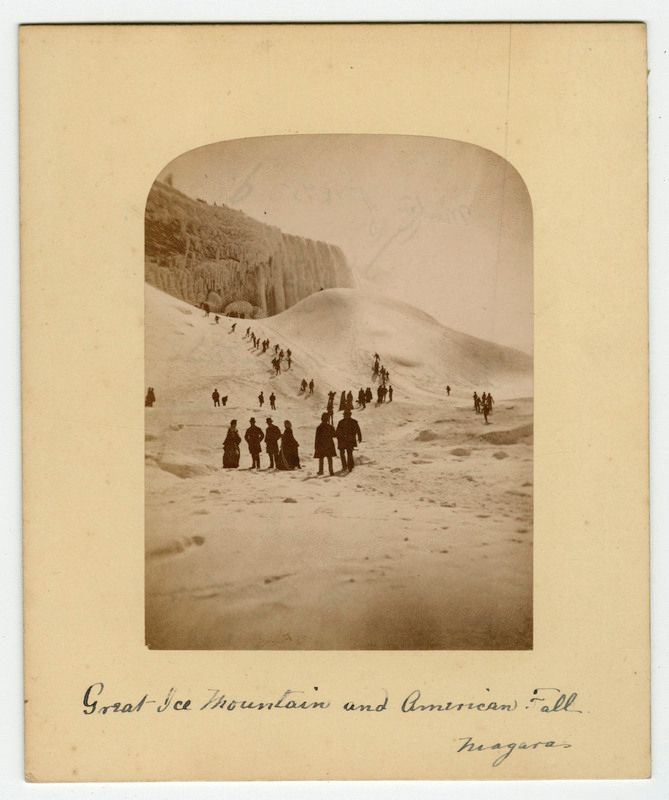

In the past, the ice mountains at Niagara Falls created a unique but often dangerous winter playground for adventurous people.

In the cold and snowy months, Niagara Falls is transformed into a winter wonderland. In frigid temperatures, the Falls can partially, though not completely, freeze over. The surrounding area also becomes encrusted in thick layers of ice. Huge icicles hang from the tops of the riverbank and natural ice bridges and mountains form in the Niagara Gorge.

An annual occurrence, ice mountains occur when northerly winds cause spray from the Falls to quickly freeze on the rocks piled up at its base. The accumulation of frozen spray results in mounds of snow and ice, which can be as thick as 100 feet and rise up just as high. Some ice mountains are nearly as tall as the Falls!

In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, thousands of people flocked to Niagara Falls just to see these captivating formations. The ice mountains became a popular site for climbing, sledding, and tobogganing. On Sundays, the railroads and streetcar lines ran special trains to the Falls and the local Salvation Army was known to hold services at the mountain’s base.

Niagara’s ice mountains were also sites of incredible danger, bravery, and heroism. Around 1880, Andrew Wallace of Niagara Falls, Ontario, either led or rode his horse to the top of the ice mountain. This was no easy task given its jagged and slippery surface! Wallace also stayed mounted on his horse for over a half hour, staring at the wintry landscape as hundreds of people watched and took photos.

On February 28, 1886, L.G. DeWitt slipped on the ice mountain and fell to his death. In order to retrieve his body, which lay about 40 feet from the top of the mountain, rescue workers had to bravely tunnel through solid sheets of ice using picks, shovels, and icebreakers. After three harrowing days, they were finally able to recover DeWitt’s body.

On January 31, 1904, hundreds of people were on the ice bridge when a large cake of ice suddenly broke away from the bridge near the ice mountain. In the process, a young boy named James Murty was sent sliding down the mountain into the freezing water. John Morrison, who was standing on the ice floe as it began to move downstream toward the Whirlpool Rapids, risked his own life to save the boy. He laid flat on the ice and when Murty resurfaced, the older man pulled the gasping boy up out of the water and onto the ice floe. Rescuers then used ropes to safely pull the floe and its occupants back to shore.

After the Ice Bridge Disaster of 1912, in which three people tragically lost their lives, it became illegal to venture out onto the icy river.

Niagara Falls Heritage Area